After 100 Years, Ramanujan Gap Filled

A century ago, Srinivasa Ramanujan and G. H. Hardy started a famous correspondence about mathematics so amazing that Hardy described it as “scarcely possible to believe.” On May 1, 1913, Ramanujan was given a permanent position at the University of Cambridge. Five years and a day later, he became a Fellow of the Royal Society, then the most prestigious scientific group in the world at that time. In 1919 Ramanujan was deathly ill while on a long ride back to India, from February 27 to March 13 on the steamship Nagoya. All he had was a pen and pad of paper (no Mathematica at that time), and he wanted to write down his equations before he died. He claimed to have solutions for a particular function, but only had time to write down a few before moving on to other areas of mathematics. He wrote the following incomplete equation with 14 others, only 3 of them solved.

Within months, he passed away, probably from hepatic amoebiasis. His final notebook was sent by the University of Madras to G. H. Hardy, who in turn gave it to mathematician G. N. Watson. When Watson died in 1965, the college chancellor found the notebook in his office while looking through papers scheduled to be incinerated. George Andrews rediscovered the notebook in 1976, and it was finally published in 1987. Bruce Berndt and Andrews wrote about Ramanujan’s Lost Notebook in a series of books (Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3). Berndt said, “The discovery of this ‘Lost Notebook’ caused roughly as much stir in the mathematical world as the discovery of Beethoven’s tenth symphony would cause in the musical world.”

In his book analyzing Ramanujan’s results, Berndt notes the existence of a solution for ![]() , but follows with, “We do not record the value here, because it is not particularly elegant.” As we will show below, a solution exists as elegant as other values found by Ramanujan himself.

, but follows with, “We do not record the value here, because it is not particularly elegant.” As we will show below, a solution exists as elegant as other values found by Ramanujan himself.

What does the equation mean? We start by comparing arithmetic sequences to geometric sequences.

Arithmetic: 1 + 2 + 3 + … + n.

Geometric: a1 + a2 + a3 + … + an.

For each type, we can predict behaviors with such things as partial sum formulas. Another form of arithmetic progression, in the realm of continued fractions, is the following:

where symbol ![]() corresponds to the Mathematica function ContinuedFractionK.

corresponds to the Mathematica function ContinuedFractionK.

The geometric version of continued fractions is known as the Rogers–Ramanujan function R. There is a related Rogers–Ramanujan function S (after Leonard James Rogers, who published papers with Ramanujan in 1919). In the lost notebook, F(q) represents S(q).

R(q) is a continued fraction of the form:

and similarly for S(q). (The presence of the prefactor ![]() makes various formulas nicer.) More formal definitions are as follows:

makes various formulas nicer.) More formal definitions are as follows:

![]()

![]()

These functions are related by ![]() . Many published works mention S(q) = –R(-q), but that’s incorrect due to branch cuts. We can also define R and S in a way that can be evaluated more quickly through q-Pochhammer symbols.

. Many published works mention S(q) = –R(-q), but that’s incorrect due to branch cuts. We can also define R and S in a way that can be evaluated more quickly through q-Pochhammer symbols.

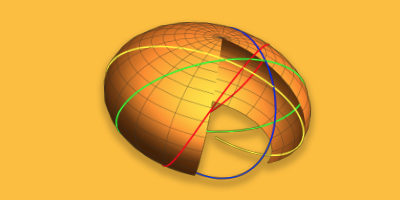

Here are pictures of the behavior of the R function on the unit disk in the complex plane. Values returned can be complex, so these pictures show the imaginary, real, argument, and absolute values (Im, Re, Arg, and Abs) of the function R(q). The unit circle itself is the natural boundary of analyticity and has a dense set of singularities of the function R(q). As one can see, the Roger–Ramanujan functions are beautiful, not just due to their mathematical properties, but also visually.

The functions R and S are two of the few named functions devoted to continued fractions. Recently, we’ve been collecting theorems and formulas for R and S, including the uncompleted ones in this piece of Ramanujan’s original “lost” notebook. That line at the end is equivalent to ![]() .

.

Many of these have been found since Ramanujan wrote them down. All of these are readily solved with Mathematica. We list the values together with the first known solvers, with solutions by Oleg Marichev being first realized by Mathematica.

Bruce Berndt noted, “The value of ![]() can be determined by using the value of

can be determined by using the value of ![]() along with a famous modular equation connecting R(q5) with R(q). We do not record the value here, because it is not particularly elegant.”

along with a famous modular equation connecting R(q5) with R(q). We do not record the value here, because it is not particularly elegant.”

With Simplify, RootReduce, and many other Mathematica functions, large equations can be boiled down to their most elegant form. Ramanujan used chalk and his mind to simplify most of his results—the long results he erased from his slate, but the elegant results he wrote down. It seems likely to us that Ramanujan actually did know the elegant solution, or at least a method to find it, he just didn’t have the time to write it down. Here’s a method we used. First, calculate a numerical value for the point of interest. Second, conjecture a closed algebraic form for this number. Third, express the algebraic number as nested radicals. Finally, check the conjectured form with many digits of accuracy.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Then we check that the numerical value of the conjectured form is the same as the value of the function. The values agree to at least 10000 places.

![]()

Since both of these are algebraic numbers with elegant representations, this is a rather convincing check. And the method can easily be generalized to find many more, so far unknown, values for S(q), and similarly for R(q).

An actual proof can be accomplished using modular equations. This is the modular equation of order 5 for S:

![]()

We use the previously known value for ![]() for S(q5) and solve for S(q) to obtain a value for

for S(q5) and solve for S(q) to obtain a value for ![]() .

.

![]()

Clearing denominators, we obtain the above form of the result.

![]()

Ramanujan’s equations are related to work we’ve done recently to add a lot of continued fraction knowledge to Wolfram|Alpha. In a future blog we will expand on the new capabilities, such as the input continued fraction K (1, n, {n, 1, inf}).

We also put together a list of hundreds of exact values in the “Ramanujan R and S” interactive Demonstration.

“Not particularly elegant”—never a good thing to say about Ramanujan. We’re glad we were able to show that Ramanujan had something elegant in mind.

Download this post as a Computable Document Format (CDF) file.

very interesting, indeed !

Bravo! Thats really very nice.

This is probably the best of all the posts in recent 1 year….!!

What a lovely tribute to the amazing mathematical genius, Srinivasa Ramanujam!

Thank you Michael Trott (love your Mathematica books) and Oleg Marichev

Wow….

simply outstanding wow

really mind blowing, thank you.

picture representation is very nice

Great mathematitian

more extraordinary scientist than Einstein…

really tremendous post