What’s Up with Daylight Saving Time? A Brief History and Analysis with Wolfram Language

In the next few days, most people in the United States, Canada, Cuba, Haiti and some parts of Mexico will be transitioning from “standard” (or winter) time to “daylight” (or summer) time. This semiannual tradition has been the source of desynchronized alarm clocks, missed appointments and headaches for parents trying to get kids to bed at the right time since 1908, but why exactly do we fiddle with the clocks two times a year?

Engage with the code in this post by downloading the Wolfram Notebook

Engage with the code in this post by downloading the Wolfram Notebook

Why Do We Have Daylight Saving Time in the First Place?

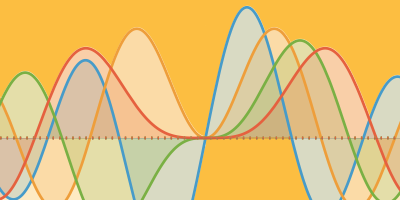

The Sun has been humanity’s primary source for measuring the passage of time for almost all of human history, and, while it’s quite predictable for day-to-day uses, it has always had a few catches that have made timekeeping over longer durations or distances tricky. Unless you happen to live at or near the equator (in which case, you have a nearly constant 12-hour day/night cycle every day of the year), you’re no doubt aware that the length of the day changes throughout the year:

![dayLength [Chicago, Today] dayLength [Chicago, Today]](https://content.wolfram.com/sites/39/2025/02/nl022825img3.png)

![dayLength [Chicago, Fri 4 Jul 2025] dayLength [Chicago, Fri 4 Jul 2025]](https://content.wolfram.com/sites/39/2025/02/nl022825img4.png)

Compare this with the same period of time for a city located close to the equator:

This phenomenon gets more pronounced the farther away from the equator one moves:

![dayLength [Glasgow, Sat 21 Dec 2024] dayLength [Glasgow, Sat 21 Dec 2024]](https://content.wolfram.com/sites/39/2025/02/nl022825img7.png)

Prior to the nineteenth century, most communities used local time determined by the Sun overhead. This variation throughout the year had little impact because time synchronization wasn’t necessary across long distances. You can see what your local solar time would read on a sundial with the SolarTime function:

![SolarTime [ ] SolarTime [ ]](https://content.wolfram.com/sites/39/2025/02/nl022825img10.png)

This is pretty close to my current wall clock time (prior to the daylight saving time shift):

However, with the progression of industrialization and urbanization favoring the use of mechanical clocks (and in particular the advent of long-distance rail travel and telecommunication), standardized time quickly became a necessity. In 1847, Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) became the British standard, placing noon at the time when the mean Sun reached its zenith in Greenwich. You can see this in the time zone offset information for London, which prior to that time used a local solar time that was a fraction of an hour off from GMT:

This was, however, not without its problems. By midsummer, some parts of the UK were seeing sunrise near 3am, while sunset was happening at 9pm:

And because people didn’t simply adjust their daily routines to match the sunlight (because they were now typically working based off of standardized mechanical clocks) this resulted in “wasted” sunlight in the morning while people were sleeping and excess use of energy on artificial lighting in the evening.

People were quick to suggest resetting the standard time throughout the year to more closely align with daylight, but the idea didn’t really catch on until World War I, where it was motivated largely by fuel preservation—and it quickly caught on across Europe. During World War II, the UK actually instituted British Double Summer Time in which the clock was moved forward two hours during the summer to maximize the use of natural light.

Compare the fraction of the summer wherein Glasgow would have a pre-6am sunrise staying on GMT compared with a two-hour shift later:

Compare the same shift difference with a pre-9pm sunset over the same time:

Keeping Up with Daylight Saving Time

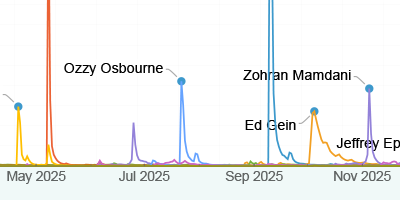

There have been many revisions to the schedule for daylight saving time within countries that observe it. There is even an entire database dedicated just to tracking these changing schedules across the globe, which is updated multiple times per year. This includes differing start/stop schedules, changes in regions that observe which shifts and which countries have opted to stop observing daylight saving time shifts altogether (typically choosing to stay on “summer time” when doing so).

Most of Mexico opted to stop observing daylight saving time at the end of 2022, for example:

To give this a try with another time zone, LocalTimeZone will identify the name of a time zone based on a location. You can also use TimeZoneConvert to identify the current time in a set location:

Changes in daylight saving time schedules, as well as the different dates on which offset changes take place, can lead to scheduling headaches for things like teleconferencing. Take, for example, the difference in time between offices in Chicago, Glasgow and Sydney throughout a period of just six weeks:

Because of the different onset and end dates for daylight saving time, nearly every week between the beginning of March and the first week of April ends up with some new difference in time zone offset between the three offices. The same thing happens again in the second half of the year when the first two cities transition off daylight saving time and the Australian office transitions back to it:

The US has also proposed (but not yet codified) a transition off of daylight saving time. Only time will tell if this semiannual tradition will continue, but in the meantime, Wolfram Language provides many tools for measuring and managing these time shifts. For more analysis on daylight times across the world, be sure to check out these posts from Wolfram Community:

This was a refreshing take on the topic, thanks!

This is one of the most helpful posts I’ve come across on the subject.