A Mathematical Snowstorm, or How I Survived a Blizzard of Koch-like Snowflakes

When I hear about something like January’s United States blizzard, I remember the day I was hit by the discovery of an infinitely large family of Koch-like snowflakes.

The Koch snowflake (shown below) is a popular mathematical curve and one of the earliest fractal curves to have been described. It’s easy to understand because you can construct it by starting with a regular hexagon, removing the inner third of each side, building an equilateral triangle at the location where the side was removed, and then repeating the process indefinitely:

If you isolate the hexagon’s lower side in the process above you’ll get the Koch curve, described in a 1904 paper by Helge von Koch (1870–1924). It has a long history that goes back way before the age of computer graphics. See, for example, this handmade drawing by the French mathematician Paul Lévy (1886–1971):

Lévy’s work “Plane or Space Curves and Surfaces Consisting of Parts Similar to the Whole” was presented to the Société Mathématique de France on February 22, 1938. But as stated in one of his notes, it was in November 1902 when Lévy had his first encounter with the curve of von Koch, which had not been discovered at that time. He defined this curve, having set himself the task of proving the existence of curves without derivatives. It’s also interesting to note that Benoit Mandelbrot (1924–2010), who coined and popularized the term fractal, was one of the best disciples of Paul Lévy.

OK, so how is it possible that I’ve been recently hit by a blizzard of new Koch-like curves if Koch snowflakes have been falling steadily for more than a century? The answer is the Wolfram Language and a tremendous passion for fractal trees. Yes, you heard it right, self-similar trees allowed me to put things in a different perspective. Few people know that a simple symmetric binary branching rule can generate the Koch curve:

That was my starting point. I set the central trunk to measure 1, so then the first pair of successive branches measured ![]() , which is the scaling factor for successive branches. For example, the four branches that stem from the initial pair of branches measured

, which is the scaling factor for successive branches. For example, the four branches that stem from the initial pair of branches measured ![]() , the eight successive ones measured

, the eight successive ones measured ![]() , and so on. Then I added five extra copies of that tree rotated in angles of 60 degrees ( π/3 radians) around the base of the central trunk:

, and so on. Then I added five extra copies of that tree rotated in angles of 60 degrees ( π/3 radians) around the base of the central trunk:

Beautiful. Then I noticed that the scaling factor r =![]() was equal to the ratio of side BC to the regular hexagon first diagonal AC, and that the angle spanned by these two segments was equal to the angle between the central trunk and the first pair of branches, 30º or π/6 rad:

was equal to the ratio of side BC to the regular hexagon first diagonal AC, and that the angle spanned by these two segments was equal to the angle between the central trunk and the first pair of branches, 30º or π/6 rad:

So I wondered if the ratio of side CD to the second diagonal AD (r=1/2) and the angle spanned between them (60º) have a Koch-like curve associated to them. To my surprise, the answer was yes:

This time, what generated the Koch-like curve was the following ternary branching rule (three branches per joint). A left branch turned 60°, a middle branch pointed downward, and a right branch turned -60°:

Again, I assembled five extra copies of it around the base of the central trunk and it generated another snowflake with 6-fold rotational symmetry:

My next move consisted of checking if the remaining diagonal had a quaternary branching rule (four branches per joint) associated with it. The ratio of side DE to the third diagonal AE is r =![]() , and the angle spanned between them measures 90º. I constrained the tree to be mirror symmetric around its trunk and to have its four branches equally spaced starting from DE:

, and the angle spanned between them measures 90º. I constrained the tree to be mirror symmetric around its trunk and to have its four branches equally spaced starting from DE:

When I added five extra copies of the resulting quaternary tree, I obtained the following intricate Koch snowflake:

Impressed by the output of these three simple branching rules, I fed a general rule into the Wolfram Language. And here is where the blizzard began. The rule was set to generate Koch-like snowflakes associated with the ratios and angles spanned by the diagonals and sides of regular polygons. For example, these are the fractal snowflakes associated with the five diagonals of the regular octagon:

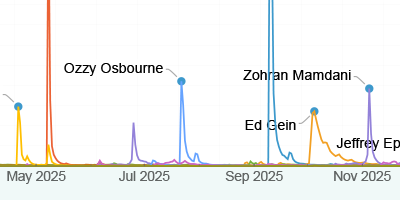

Now you keep counting: the nonagon, the decagon, the hendecagon, and so on up to infinity. And don’t forget to count the infinite sides of their limiting element, the circle. So the question is how did I survive the blizzard? I stopped the snowflakes from falling. I managed to trap them all in this map:

Don’t panic; this diagram is really easy to understand. The points on the lower horizontal line are the end points of the first pair of branches that generate the binary trees that make Koch-like snowflakes. For example, the point labeled as H(5,2) generates the following tree:

This tree has 5-fold rotational symmetry when four extra copies are assembled around the base of its trunk:

So now you might be wondering what happens if the first pair of branches are not exactly set at these points. Well, if the branches are still lying on the horizontal line, the tree generates a Koch-like curve, but it can no longer be assembled to make a snowflake:

The points on the horizontal line are the points that define binary branching rules to generate snowflakes of n-rotational symmetry. And these snowflakes are associated with the regular polygons’ first diagonal. Here is a table that shows what these snowflakes look like:

The diagram is that simple. The curve above the horizontal line is where Koch-like ternary trees live. Quaternary trees live in the next one, 5-ary trees in the next next one, and so on.

The next time a blizzard keeps you home, don’t just stare out the window at the snowflakes. Hop on your computer and reach infinity in less than an hour.

Download this post as a Computable Document Format (CDF) file.

Really Beautiful Bernat.

It is amazing that nature and now computers can discover so many nested planar patterns.

Thanks for these new compiled snowflake programs.

Michael

Thank you Michael!

You may be interested in the discrete global grid system (a type of GIS) built on square root 3 tiling of the Icosahedral Snyder Equal Area Aperture 3 (ISEA3H) hexagon grid. It uses the tiling structure shown above to index the globe:

Ping me if you are interested in seeing it in action.

Regards, Perry Peterson